|

Articles

21 Nov 2018 DASSAULT SYSTEMES. The French success story in the software industryFrancis BERNARD

Francis BERNARD—Cofounder (1981), President (1981–1995), Executive Vice-President & Board Director (1995–2006)

This document describes the extraordinary success story of the Dassault Systèmes company, from the origin in Dassault Aviation in 1967 until my retirement in 2006

1– INTRODUCTION

I graduated from Ecole Nationale Supérieure de l’Aéronautique (Supaéro), a French Aerospace University, as an aircraft engineer, in 1965.

I believe that my generation has been lucky in several ways:

- We were born during the war, but then we had a long period of peace, during our education and our professional life,

- We faced a dramatic evolution, especially in the Information Technologies, the “IT revolution”. It has been an incredible change in our professional and private life with the computer, software and telecommunication technologies. And such exponential evolution is not going to slow down,

- The globalization, together with the end of the cold war in the late 80’s, gradually erased the borders, opening up the market opportunities for alliances and unbelievable cultural mixing.

I took full advantage of such favorable environment, all along my professional life. It has been like a dream… It gave me the opportunity to become the “father” of one of the most famous software product in the world, CATIA, and the founder of the greatest success story of the last 50 years in the French software industry: the Dassault Systèmes company.

My professional life went through two complementary phases: fifteen years in the aircraft industry with Dassault Aviation, then twenty-five years in the information technology with Dassault Systèmes until my retirement. I am still active as an Executive Advisor, and/or a Board Director, involved with the development of several small companies, but this is not the subject of this document, and I am not going to address it.

Let me briefly outline this story… how, by using a very representative metaphor, we have created a tree (1995) starting from a seed (1967), which grew up has a plant (1980), then a shrub (1981)…

2– DASSAULT AVIATION

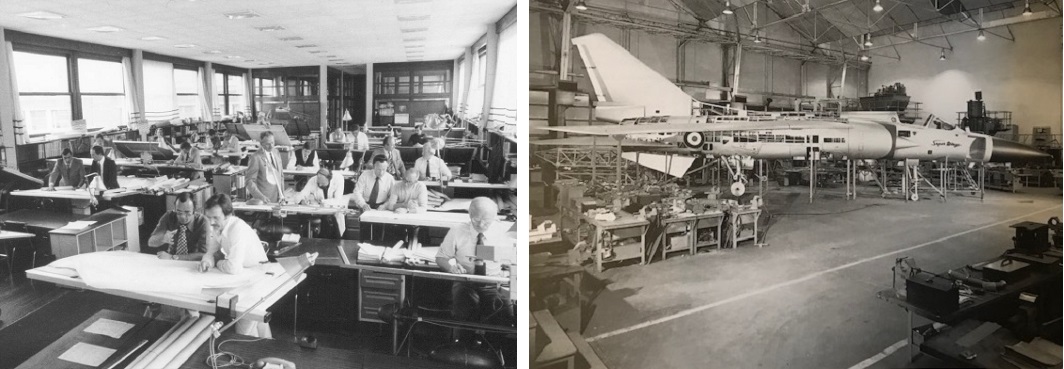

After my military service, I entered Dassault Aviation (called at this time “Générale Aéronautique Marcel Dassault”) in February 1967. During such period, Dassault is a prestigious enterprise in the domain of military airplanes, with the extraordinary success of the Mirage III. The right place to be within Dassault Aviation, when you are an ambitious engineer in the 60’s, is the Design Office. This is where you learn how to design at scale 1/5 a new airplane, using a pencil, a paper and a drawing board. And a scale 1 mockup made of wood is built to verify in “physical 3D” the internal structure and parts assembly. But I preferred to join a newly implemented Advanced Studies Division, more precisely in the Theoretical Aerodynamics Department. In such department, you enjoy playing with sciences and mathematics.

The Design Office in the 60’s; the 3D mockup in the plant floor

At Dassault Aviation, the activity is incredible during the 60’s and 70’s. We design and build a new military airplane almost every year for the air force: Mirage III, Mirage IV, Mirage V, Mirage G, Mirage F, Alpha Jet, ACF… We can see the change compared to nowadays. During the cold war, the threat from the east was strong enough to justify the launch of new airplanes, either as advanced demonstrators or for mass production, nearly every year. Nowadays, this short yearly time unit has been extended to decades and may become a half-century! Also, Dassault develops a new generation of advanced Business Jets: Falcon 10, Falcon 20 and a commercial mid-range, twin engines jet: Mercure. Such commercial jet has been the unique attempt of Dassault to enter the commercial market, now in the hands of Airbus. Nowadays, because of the decline of the military market, the main and very successful business of Dassault Aviation is the Falcon products line.

An airplane must be optimized to fly securely as fast as possible, as far as possible, at the lowest possible cost, according to its mission. This means that we must be at the leading edge of innovation and technologies, to compute and optimize the behavior of the airplane. And we can afford it because we are a rich company, well managed by our mythical founder Marcel Dassault. We are therefore the first enterprise in France to invest massively in computers and software in the early 60’s. We install in 1967 the two first interactive graphic terminals in Europe, called IBM 2250, connected to the first generation of the IBM mainframe computers, called IBM 1800, able to run scientific computation. All the programs and data are entered with punched cards.

But with the first computers, there is no software to run any application. It is only a huge hardware device with a basic operating system. We know how to manipulate mathematics, we know how to predict a theoretical aerodynamic flow with a set of equations, but we have only a rudimentary knowledge of software development. Therefore, we progressively learn how an aerodynamics specialist must become a software developer using the Fortran programming language to resolve aerodynamics problems.

And then we have another challenge: how can we define, with the computer, the shape of the airplane, which is the input to aerodynamics analysis? How can we define a curve, a surface, with the mathematics and then with the software?

We start with the curves. The draftsman in the Design Office uses a flexible plastic curve ruler to draft a curve, which is going through a given set of points. I invent a mathematical representation, which is a succession of 5th degree polynomials with a continuity of the curvature derivative anywhere along the curve, and which reproduces the shape designed by the draftsman.

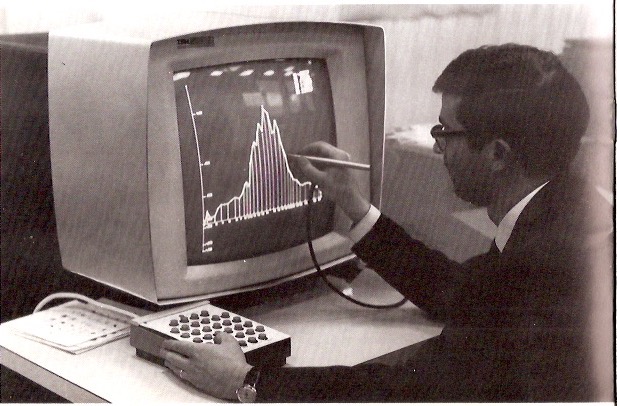

Curve smoothing

And I develop in 1967 the first interactive graphic “smoothing program” visualizing the curvature distribution. The manual or automatic modification (under tolerance constraints) on each entry points allows smoothing and controlling the curvature evolution along the curve.

Fifty years later, I realize today that I was, without knowing it, the first of the thousands who are going to be Dassault Systèmes and that this program is the first microscopic element of its solution. Like in nature, it is the tiny seed within thousands of others, which is the unique origin of a big tree. Without such seed, there would not have been the tree; Dassault Systèmes would not have existed…

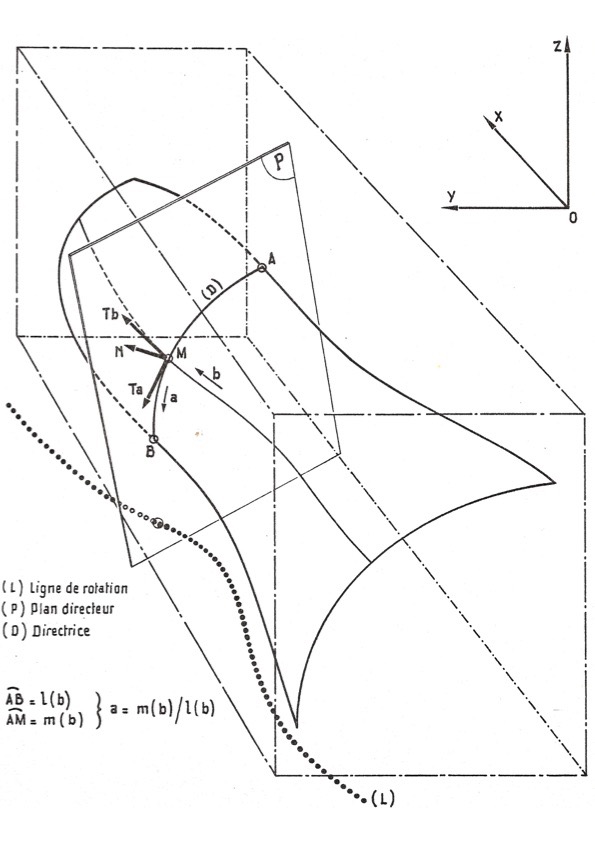

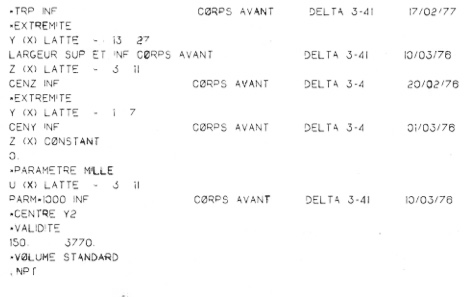

Then we address the surfaces. I manage a small team within the Theoretical Aerodynamics Department and in 1968 we start reproducing with the computer the methodologies used by the draftsmen in the Design Office. The wings are ruled surfaces generated between profiles, which are the outputs of the smoothing program. The fuselages are surfaces generated by conics. Their parameters (generally the end points and tangents and a middle point) evolve along the axis of the fuselage according to curves stored by the smoothing program. In the early 70’s, we start developing the MIRA program, which allows to describe each surface with an alphanumeric language on punched cards and store such implicit representation in the data base of the fuselage. And in the same time, we develop several programs to extract the appropriate information from the database, especially the ORION program that generates sections by any specified plane.

|

|

|

Surface by conics evolution

|

Creation language

|

This has been the emergence of CAD (Computer Aided Design). We called GEOVA (Generation et Exploitation par Ordinateur des Volumes d’Avion) the set of programs dedicated to CAD.

I remember a story which may have influenced my future and which may be at the origin of CATIA. In December 1972, Marcel Dassault calls the Technical Director, Henri Deplante, at his desk. As a matter of fact, the prototype of the Falcon 10 crashed in October and the boss wants to know how it happened and what are we going to do to fix the problem. We are in the last week of the year, between Christmas and New Year. Everybody is on vacation, except me. I am very young and immature but the only engineer at work. Therefore, Henri Deplante asks me to come with him. I show on the floor the profiles of the wing on a large piece of paper. Marcel Dassault asks me: “What is it?”. I tell him: “These are profiles of the wing designed, optimized and drafted by the computer on this paper.” For the first time, the big boss discovers the output of the computer technology.

CAD, born from an aerodynamics requirement, becomes a mandatory tool within the company. In the early 70’s, I am heading a small team, then in 1975 a department with ten engineers and technical specialists, and then in 1980 thirty engineers to define numerically the shape of the airplane, for the aerodynamics specialists and the stress analysis specialists, and finally also the Design Office.

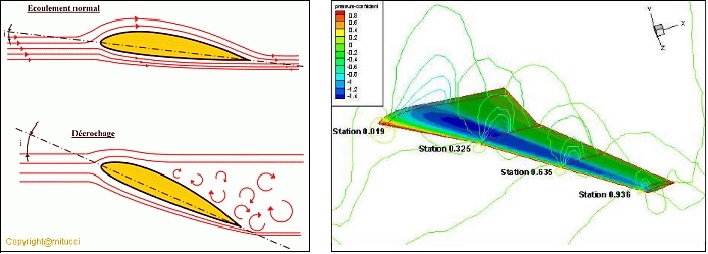

Aerodynamics analysis

In the plant floor, specialized draftsmen draft very precisely, at scale 1 on sheet metal, the shapes which have been defined on paper at scale 1/5 in the Design Office. This job will disappear progressively in the 70’s and 80’s together with the implementation of the computer technology. During the same period, we install the first Numerical Control (NC) machines in the manufacturing plants. These machines are used to carve in thick solid aluminum blocks the most complex structural parts of the airplane. It is a requirement, particularly for the military aircrafts, to get the best performance with the lightest structure. From the CAD definition of the shape of a complex part, with the APT language we define the paths of the machine tool and then download such information to drive the NC machine.

NC milling of a Mercure structural component

This is the birth of Computer Aided Manufacturing (CAM). The integration, on the same database of CAD and CAM has been called CAD/CAM. For the first time in the industry, the exact same geometry data are used for Design, Analysis and Simulation, and Manufacturing, eliminating all the transcription and interpretation mistakes along the design and manufacturing processes.

In the early 70’s, the two first airplanes of which the skin and the main structural parts are designed, optimized and manufactured with our CAD/CAM solutions are the Mercure (a commercial airplane) and the Alpha Jet (a Franco-German military trainer). I remember several trips to Friedrichshafen, on the edge of Lake Constance in Germany, to meet our partner Dornier. The shapes were defined by Dassault and we were transferring them our numerically defined data base to optimize our teamwork.

|

|

|

Mercure

|

Alpha Jet

|

Since my early days at Dassault Aviation in 1967, one can understand how we took advantage of the technological innovations from computers, interactive graphic terminals and numerical control machines, within the extremely favorable environment of an innovative enterprise addressing a dynamic commercial and defense aircraft market. We initiated a new way to design, to simulate with aerodynamics and stress analysis and to manufacture with NC machines.

More generally, most of the aircraft industry took a leadership position in the CAD/CAM revolution, in the USA as well as in Europe. As a matter of fact, the mandatory requirement is to optimize the airplane through calculation, and to use the numerical control machines to carve the main structural components.

In 1975, our Design Office makes the acquisition of CADAM, a drafting system developed by Lockheed, an aerospace company based in Los Angeles in the USA. It is a small revolution, which is going to be very well accepted by the draftsmen, replacing the drawing board by an interactive graphic terminal, without any change in the design process. Such 2D CAD system improves significantly the precision, productivity and quality of the work. And we develop interfaces to transfer the planar sections of the 3D shapes to CADAM as well as some enhancements in CADAM, especially in the 5 axis machining capabilities.

In 1977, we had under the name of DRAPO (Dessin et Réalisation d’Avions par Ordinateur), the GEOVA set of 3D CAD/CAM programs developed by my team, and CADAM for drafting. All our airplanes were progressively designed and built using these software programs. But it was a set of tools, developed step by step according to specific and urgent requirements, with a relatively low level of integration. Also, it was rather complicated to use the software. As a matter of fact, we were still dependent on punched cards and alphanumeric language for most of the applications, such as for instance intersecting two surfaces, because the computers and graphic terminals were too slow to allow an easy intuitive real time user interface. You had to be a specialist to use the software. Therefore, we operated this way: my team developed the software and used it upon request of the engineers of the other departments of the enterprise. For example, a designer of the Design Office would request a section of the wing by a given plane; my team would execute the job with our computer programs and deliver the requested section curve on paper, drawn by the computer on a drawing machine, or as a CADAM file. In other words, the 3D CAD/CAM was not yet fully integrated and deployed within the internal working processes of the enterprise.

The only way to make a new step to reduce significantly the Design and Manufacturing cycle time was therefore to make it easy for the non-specialists of all the departments of the enterprise to use the 3D CAD/CAM software as their own tool. The top management was extremely eager, for instance, to reduce by a factor 4 the Design and Manufacturing cycle time of a new wind tunnel model of the aircraft. This would allow testing 4 times more variants of the same airplane, before launching the detail design of the best variant.

In 1977, with the full support of my management, I decide to launch the rewrite all our software, on a single architecture and with a full interactive graphic interface, in order to make it easy for non-specialists. The computer technologies had evolved considerably in the last ten years, and we have now more powerful mainframes (IBM 360) and a new generation of graphic terminals (IBM 3250). It is possible to compute and visualize 3D elements like surfaces in real time… despite we are still very far from the PCs of today. As a matter of fact, the computation time may be quite long if there are too many active users connected to the same mainframe and the graphic terminals visualize only a limited number (approximately 2000) of white segments on a black screen. But this is the normal evolution of technologies; the leaders catch as soon as possible any favorable step, even if such step looks quite basic a few years later.

The new software must be 100% graphic, interactive, intuitive, 3D, easy to use by non-specialists.

How should we name it? After some thought and discussion with my team, I decide for CATI, an acronym that is valid in French as well as in English, which means Computer Aided Tri-dimensional Interactive application. A few years later, when we decide to market it, we discover that CATI is already a trademark in the USA, so I am adding A to call it CATIA, for Computer Aided Tri-dimensional Interactive Application.

I therefore launch the development of CATIA in 1977, with only four software engineers… As requested by our management, the first application of CATIA is the design and manufacturing of a wind tunnel model. And we demonstrate in 1980 a dramatic cycle time reduction.

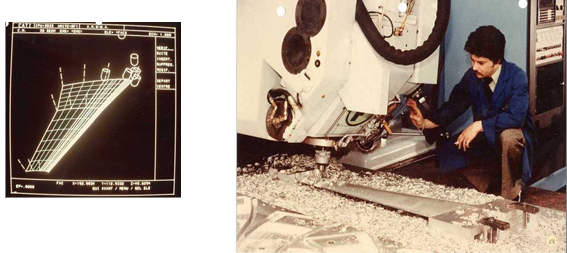

NC in CATIA… wing of a wind tunnel model… NC in the shop floor

Progressively everybody knows CATIA in Dassault Aviation. It is like a miracle for many people: you can design within a few minutes a curve, a surface, a structural component, rotate it, and cut it, in 3D. You can position the cutting tool of the numerical control machine, define its path along the part, and simulate graphically in 3D the machining process. You see the reality; you don’t need to figure it trying to interpret a drawing. Nobody in the world had expected such kind of capability, which is nowadays a commodity even at home.

How could I imagine that CATIA would become a global standard implemented by the aircraft manufacturers, then by all the industries? For me, for my team, CATIA was in 1980 only one of the hundreds new software used by Dassault.

I believe that any major innovation is, in a technological and cultural favorable context, the response to a need that is rarely expressed or even perceived by future users. You need to match the understanding of the pains supported by the users, together with the capabilities offered by new technologies, to figure out the products for tomorrow. My team was in the best position to catch the challenge because we had an understanding on both. Indeed, before CATIA became the tool of the Design Office, we had to overcome the reluctance of all the design engineers, from the top to the bottom of the hierarchy, who believed that the 2D drawing could never be replaced. They were already starting to use the computer to replace the drawing board with CADAM. It gave some quality, precision and productivity benefits, compared with the drawing board. But with CATIA, we implemented a complete business transformation, allowing the full integration of Design, Analysis and Simulation, Manufacturing, based on a single database. It has been a dramatic cultural transformation on the way to design and build an airplane, with a huge improvement on cost, cycle time and quality.

At the end of 1980, the CATIA rumor goes to the very top of the company and Marcel Dassault, the 88 years old mythic founder of the company, ask for a demonstration of the software capabilities. He looks at the design of a surface on the terminal and, after a few minutes, he tells me: “Let me work by myself.” A picture immortalizes this moment: we see Marcel Dassault, Dominique Calmels, my technical manager, and myself on the right. Marcel Dassault is an engineer; he understands immediately the value of our software.

Marcel Dassault, Dominique Calmels, and Francis Bernard

We have lived the three phases of the expression of design:

1– Until early 70’: drawings on paper and drawing boards,

2– From early 70’ until early 80’: computer technology reproducing the methods of drawing (GEOVA, CADAM). We cannot yet eliminate the scale 1 wooden mockup of the airplane but simulation and manufacturing are integrated with design, the quality is improved considerably, and the cycle times are reduced,

3– From the early 80’s: computer graphics, interactive, full 3D and accessible to everybody. We are again improving quality, productivity and, most important, we are able to create a 100% 3D digital mockup of the airplane, including all the internal components, in the early 90’s.

CATIA becomes so visible and promising that the management of the company starts to debate on how to leverage such innovation. Do we keep the product internally, taking advantage of its benefits against the competition, or do we decide to make it a new business of the Dassault Group and sell it outside the company?

The first option is a dead end. As a matter of fact, I have only fifteen CATIA developers in my team, at this time, but how could we afford to fund in the future the hundreds developers we would need to address all the necessary functionalities, only for one single company? Obviously, we would have to replace sometime CATIA by a product that we could buy when the CAD/CAM software market is mature enough.

We control the technology and we have the Version 0 of CATIA. But we have no experience on sales and customers support, we don’t have any sales structure and organization.

We know that the competition is mainly American, extremely strong and benefiting from a very large domestic territory, at least ten times larger than France. CADAM (we are a direct customer but now it is sold by IBM since 1978), Computer Vision (worldwide leader), CALMA (from McDonnell Douglas), APPLICON… are already well established with hundreds of employees, hundreds of customers, when we have a small team and a single customer, Dassault Aviation. And who knows Dassault, abroad and especially in USA and Japan, except in the aerospace community?

We look at several opportunities. At the end of 1979, we investigate a potential alliance with SNIAS Helicopter Division (a government-owned company). They have developed a software called SYSTRID, dedicated to surfaces design, which runs on IBM platform. The French government could participate financially. In 1980, we also investigate a potential alliance with Lockheed to integrate CADAM and CATIA, because they are complementary products running on the same IBM platform, and to implement a common subsidiary to develop, to sell and to support the solution.

And we will end-up with a third alternative… simpler, more attractive… It is to create a new company to develop and to sell CATIA worldwide in all sectors of the industry, if we can set up a worldwide sales agreement with IBM similar to the already existing agreement between Lockheed and IBM for CADAM.

The seed, which was the smoothing program and myself in 1967, became in 1980 a plant with a small team and the first operational version of CATIA. It benefited from the favorable Dassault environment: technology at the top level, and massive investments in computer technologies to optimize fighter aircrafts.

3– DASSAULT SYSTEMES

Dassault Aviation is one of the biggest clients of IBM in France, perhaps the biggest in the scientific and technical domain. In the early 80’s, IBM is by far the worldwide leader in the computer industry, with more than 80% of the market share. It is the great period of the mainframe computers; there is not yet any PC, no Microsoft. Also, IBM has signed in 1977 a worldwide distribution agreement with CADAM Inc. to sell CADAM together with its mainframe computers and graphic terminals. As a matter of fact, CADAM is for IBM an excellent catalyst to generate significant hardware revenue because the software is running only on the IBM platform.

It happens that I have a good relationship with our IBM salesman, a very dynamic personality. And I propose him a similar deal between IBM and Dassault, where IBM would sell worldwide our software, together with its hardware. The IBM software portfolio would include CADAM for 2D applications and CATIA for 3D applications, with a relatively good level of integration, as long as CATIA includes a CATIA–CADAM data transfer interface.

For Dassault, such deal is mandatory. We cannot go on the market without a sales force, we need a worldwide coverage to compete against the American competition, and we don’t know how to sell and to support a software product. Getting the skills and experience by us and building the appropriate worldwide organization would take too much time to survive. This is a mistake, which has been done by our French competitor at that time, called Matra Datavision.

Also, the IBM brand name adds a significant credibility to our offering; it is like Coca Cola in the IT industry, IBM has 80% of the worldwide hardware business.

My French IBM friend takes the challenge. At that time, all the IBM decisions are negotiated at the level of its Headquarter in the USA. So, he flies to New York and get in touch with all the IBM executives who may decide. And he does really his job of sales man, this time not to sell a piece of hardware to a customer, but to sell a French software opportunity to the IBM American Company. He succeeds to generate attention. IBM sends two technical specialists to evaluate CATIA. They do some tests in CATIA, such as the design of a rod, which is a quite complex part at this time.

After the elimination of two other options in USA (Northrop), and in Japan (Toyota), IBM executives fly to Paris to negotiate the deal with Dassault Aviation. Charles Edelstenne, CFO of Dassault Aviation, leads the negotiation, which will end successfully with a worldwide IBM–Dassault agreement signed in July 1981. It is a nonexclusive, 50/50 revenue share agreement where CATIA is sold by IBM as an IBM product. This deal has been extremely successful for both companies; it has been one of the fundamental drivers of the Dassault Systèmes success story. And it lasted for nearly 30 years. As IBM progressively reduced its hardware business, and Dassault Systèmes became a strong worldwide organization, the partnership ended smoothly without any crisis when Dassault Systèmes acquired the IBM Sales force dedicated to its solution at the end of 2009.

In 1981, the value of such agreement is not so well perceived. I remember the French authorities asking me why I make an alliance with an American company and some American executives questioning if it is appropriate to make a deal with a semicommunist country, especially during the cold war at that time… as a matter of fact, there were a few communist Ministers in the French government.

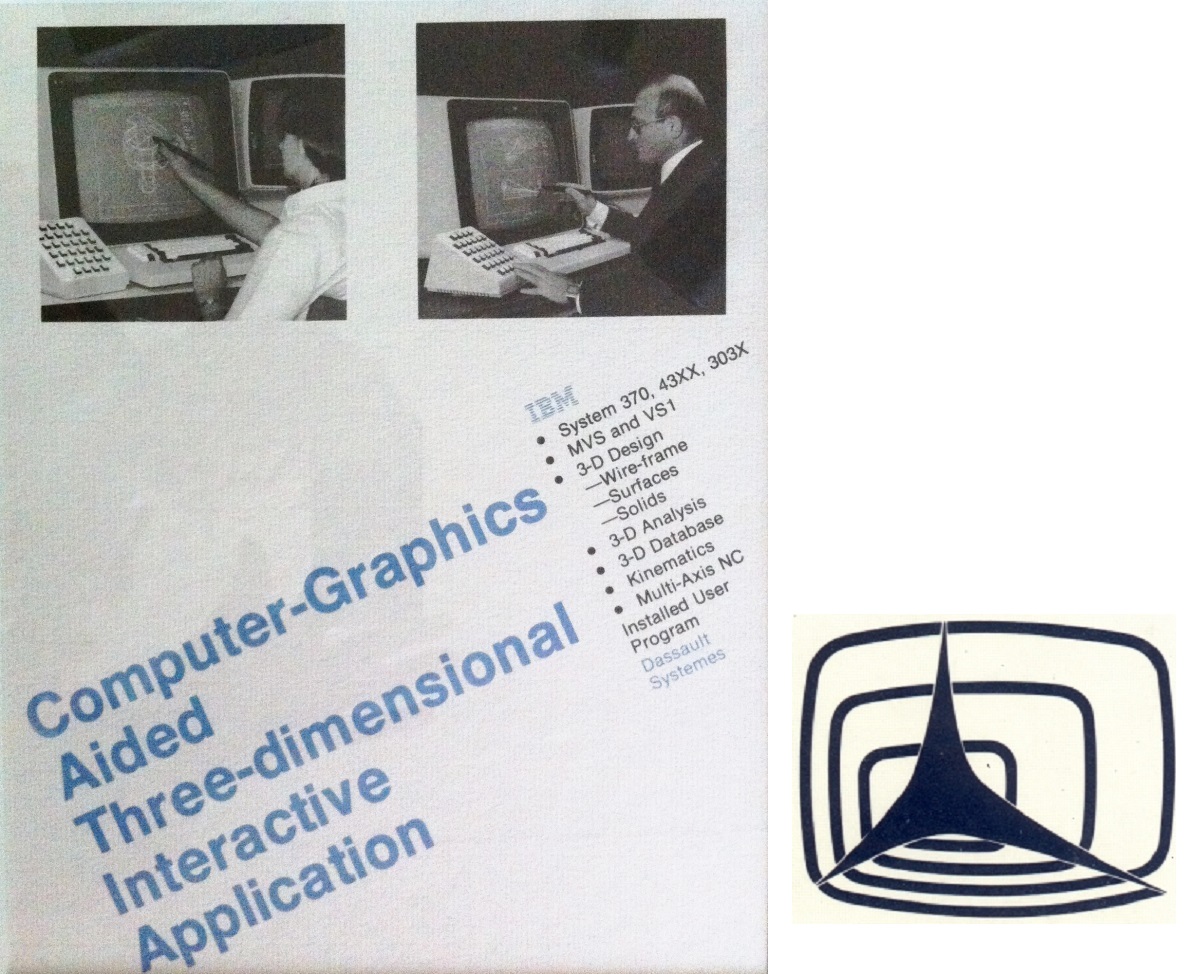

The first IBM flyer and the first logo

We need to give a name to our new company, at this time a subsidiary of Dassault Aviation. It takes just a few days to decide for a name, Dassault Systèmes.

And I sketch our first logo with a symbolic representation of the graphic screen and 3D.

We launch the company operations in September 1981. I am the President and 22 engineers of my team in Dassault Aviation move with me in Dassault Systèmes. A few people prefer to stay with Dassault Aviation, just because they believe that we engage in a too risky adventure… Charles Edelstenne is the Chairman, a position that he has still today.

The plant has now become a shrub… we are a company dedicated to CAD/CAM, we have a competitive and innovative solution, and we have with our partnership with IBM a worldwide sales organization…

Within a few months, my first customers were Honda in Japan, Mercedes and BMW in Germany, SNECMA (now SAFRAN) in France and Grumman Aerospace (now Nothrop Aviation) in USA. We delivered CATIA under a direct license agreement to these five first customers because they were extremely eager to evaluate CATIA as quickly as possible under their technology evaluation strategy. We discovered with them new cultures and industries and they became unbelievable references before their migration to IBM a few years later.

It has been a challenge for several reasons:

1– The world globalization that we experience today did not exist yet. Our customers in Germany and in Japan didn’t speak English, and ourselves we could speak only very poorly… Flying to Japan was an adventure, a 20 hours flight with a stop in Anchorage (Alaska) and no English signs in Tokyo… Even a telephone call between Paris and New York was an event… And of course there were no emails, no Internet. We became unconsciously the actors of globalization.

2– The industry was still using massively the 2D drawings as its standard for Design.

3– We knew well the aircraft industry, but we didn’t know anything about the automotive or any other industries.

How did we achieve success? From our experience within Dassault Aviation, we knew that we would face a strong resistance at a time when all the CAD/CAM vendors were selling mostly a 2D solution. Therefore, we decided to escape from selling functions, features, and discussing detailed requirements with our prospects. We decided to sell a complete business transformation, “a revolutionary new way to design and manufacture”.

With such strategy, we escaped from fighting in a battlefield dominated by our strong competitors when we were still a start-up company. By selling a business transformation, we talked at a higher level of the organization of our customers, most of the time at the CEO and CTO level. And we were perceived more like a partner that a vendor.

Our challenge was to demonstrate very quickly a dramatic innovation, with short-term benefits on cycle time and quality, and mid-term benefits on cost. We established a close relationship with the customers to help them implement the business transformation, with major impacts on their way to design and build, instead of implementing only a new tool. And of course, we tried hard to meet all of our commitments on time to generate the confidence in our capabilities to execute.

We also learned fundamental lessons to become a software editor:

- A software product should not be specified only by analyzing functions and features with customers or competition analysis. This is a “me too” strategy and the risk is also to develop customers specific products instead of market specific products.

- Mixing innovation through research and new technologies, with a good understanding of each industry segment processes is the only way to define the specifications of the future successful software products. And of course, the challenge of the editor is to demonstrate value of his offering.

- A software, even very up-to-date and competitive, must evolve permanently. Otherwise it quickly loses its competitiveness and its capability to be compatible with the evolution of the hardware and software on which it is based. The relationship with the customer is therefore a long-term relationship requiring permanent investments of the editor financed by recurring revenues from its customers, up to at least 50% of his total income. It is also a protection against difficulties such as an economic depression or a crisis in a market that can slow down the sales performance on the period.

In the early 80’s, we had a very poor knowledge of the automotive industry. We did not know enough about their internal processes to sell anything else than function and features in 3D. Hopefully, Honda, Mercedes and BMW had set up an internal team to study the values of 3D and the ways to implement it. Working with these teams, they learned from us the value of 3D and we learned from them the internal processes of Body design, a domain where the automotive industry could use CATIA nearly “as is”. And progressively we created the confidence, they started to deploy CATIA in Body design and we influenced the CATIA development plan to be more competitive in this domain. Later we extended our partnership to address progressively all the automotive processes. The benefits have been incredible, reducing by a factor 10, from 1980 to 2000, the cycle time to produce a new car.

In 1985, CATIA had become the leader in the German automotive industry.

China… I am one of the first IT business man flying to Beijing in 1985, to negotiate the sale of CATIA to the Ministry of Aviation. I remember the old fashioned, dilapidated, and very small airport, the Russian car from the ministry waiting for me, the narrow road to go to the only hotel from the 30’s for visitors in Beijing, the “Beijing Hotel” near the Forbidden City. No cars and millions of bicycles. IBM had a small team in Beijing and, as we were under the cold war, IBM could sell only the low-end mainframes with a case by case authorization from the US administration. Some people in France were joking about my trip: “What are you doing in this country?” And now, China is a huge CATIA customer…

In 1986 we had a great success: Boeing made the decision for CATIA. And this success reflects exactly the comments above. As long as I was selling with IBM the functions and features of CATIA, I lost the battle in 1984, 1985. My main competitor was an internally developed product. But when I sold the business transformation, with all its benefits, then I had a meeting with the CEO of Boeing. And he told me: “Tell us how we can design an airplane in 3D, this is what we need.” CATIA was only in the background and I used my experience from Dassault Aviation to convince the CEO.

Also, frankly speaking, he told me: “I buy CATIA and the relationship with you because you are with IBM.” As a matter of fact, Boeing could not implement a huge business transformation without a big name like IBM in the loop. This was one of the values of the partnership with IBM.

Furthermore, because of the huge potential issues for Boeing and the cold war in the background, we were requested to deliver the source code, to be secured in a gold mine somewhere in the USA territory, just in case Dassault Systèmes disappears.

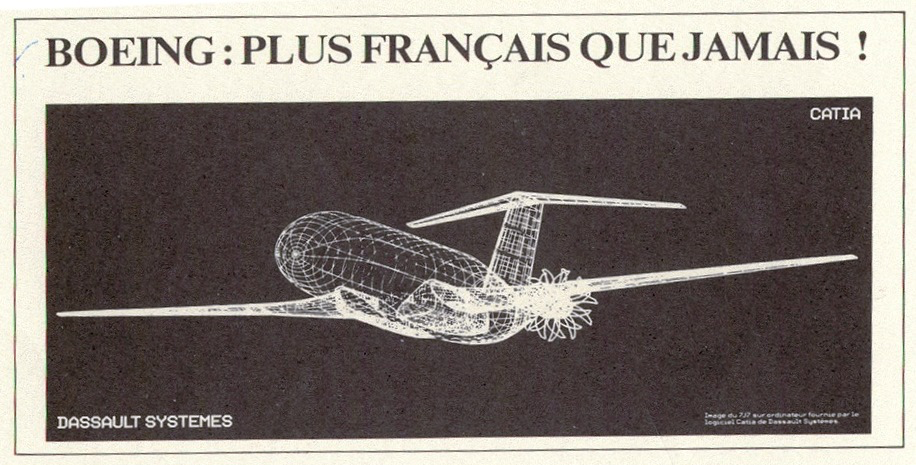

The deal with Boeing generated a huge attention in the world. I was invited to speak at the main radio channel in France. And Boeing, a strong competitor of the French Airbus, bought half pages, during one full week, of the most important national newspapers advertise “Boeing is more French than ever!”

The Boeing advertisement

IBM became our internal customer in 1986 and deployed CATIA in all its engineering and manufacturing plants. In 1988, Chrysler became our first automotive customer in USA.

During the 80’ and 90’ we extend our solution to address design, simulation, manufacturing integrated on a unique data base. Progressively, our solution becomes the de facto standard in the aerospace industry, and by far the leader in the automotive industry. And we used a step-by-step approach to progressively address all the other industries such as Consumer Goods, Machinery, and Shipbuilding.

In the same time, IBM develops a worldwide organization dedicated to the Dassault Systèmes solution. IBM addresses the “large accounts” (approximately 450 enterprises in the world) and manages a large network of remarketers to address the small and middle size accounts. We become an IBM remarketer for our solution in France and all the countries where we have a subsidiary.

We have Version 1 of CATIA in 1981, Version 2 with 2D drafting capabilities in 1984, Version 3 in 1988. In 1990–1992, we are facing a strong competition against a new American comer, Parametric Technology (PTC), which introduces a major extension to 3D with the parametric geometry capabilities: the user can change any pre-defined dimension of a part and the software modifies automatically the part. This competition reduces dramatically our growth and even Boeing is about to migrate to PTC. Hopefully, in 1993 we resolve the problem with Version 4 which includes parametric geometry. Then we launch Version 5 in 1996.

Version 1 contains 5 products, and Version 5 more than 50… and with Version 3, we sell a development platform (GII, Graphic Interactive Interface), which allows R&D partners to develop and to sell applications, which are integrated into our solution. We also sell a first version of relational database (CDM, CATIA Data Management).

CATIA evolve also to benefit from the new hardware and software platforms: at the beginning, the IBM and IBM compatible (Amdahl, Fujitsu) mainframes with MVS then VM operating systems, in 1983 the IBM 5080 graphic terminal displaying shaded pictures in color, in 1988 the UNIX based workstations IBM or IBM compatible (SUN, HP, SGI), then in 1996 the PCs with Windows, and now Internet extends again the potential.

We were 23 people when we started Dassault Systèmes in 1981. Then we managed a regular but extremely fast growth, with 200 people in 1985, more than 500 in 1990, and more than 2000 in 2000. Our first subsidiary has been set up in USA, near New York, in 1984, and then it has been extended to Detroit and Los Angeles. We set up a subsidiary in Germany (1988), Japan (1992), Korea (1998), China (2002), Russia (2005). We create in Paris a services company called Dassault Data Services in 1988… We have people assigned within IBM (Japan, Germany, USA) and a few large customers. We implement subsidiaries all around the globe to be close to the local IBM organizations and our customers. We have tens of thousands of customers.

In October 1991, we celebrate our tenth years anniversary with all our people in a prestigious place in Paris: we are with IBM the number one in the world. We have 20% of the market, with 4000 mainframes and 15000 UNIX based workstations. We are the leader in the automotive market (40% of our installed base) and the aerospace market (30% of our installed base). Our revenues are 50% from Europe, 25% from North America and 25% from Asia.

Most of our competitors in early 80’s disappeared. Computer Vision, the worldwide leader, made the strategic mistake to develop its own proprietary hardware when the market requested standard platforms. CADAM made the strategic mistake to stay in 2D when 3D became the revolution. IBM acquired CADAM in 1989, then we acquired CADAM from IBM in 1991 against a 10% IBM share in Dassault Systèmes. Matra Datavision, our French competitor, made the strategic mistake to implement its own worldwide sales organization, which is an extremely slow and expensive process. They disappeared in the early 90’s and we acquired and integrated some of their R&D teams.

We inherited, from the relationship with IBM and with our key customers, a strong culture of partnership. The general idea is to extend and reinforce our strength, in term of functionalities coverage, technologies, customer’s support, research, or sales, not only with our own resources but also with partners. Progressively, we have built an Ecosystem with hundreds of partners. Looking at the ecosystem of an enterprise is, for me, a key parameter to measure its strength or its weakness.

In 1995, Dassault Systèmes entered the stock market… during the internet bubble in 2000–2001, we became one of the top 40 French companies in term of capitalization…

And we accelerated the growth with well-positioned acquisitions…

The shrub has become a tree…

It is said that trees do not rise to the sky. Our tree will die someday, in a century, perhaps? But it also makes a lot of seeds, and it contributes to the forest of the future… just as Dassault Systèmes was born from a seed of Dassault Aviation, I already know some seeds from Dassault Systèmes that have become plants… Companies are like humans, they are born, they create, they reproduce and they die one day…

I left my position as General Manager in 1995, leaving the position to a very talented young engineer whom I had hired in 1984 and then promoted gradually to the top, Bernard Charlès, but I stayed in the senior management team focusing on emerging markets by industries (such as shipbuilding) or by geographies (China, India, Russia, Turkey, South Africa, Indonesia, …).

On September 11, 2001, I was in Ulsan in Korea visiting Hyunday Heavy Industries, the number one shipyard in the world… and I discovered the attack on my hotel room TV, just before spending the day with my customer.

I experienced the fantastic development of China, from my fist visit in Beijing in 1985 to sell our first CATIA licenses to the Ministry of Aeronautics, until today, at the end of 2005, where we have a well-established subsidiary and many customers. And also, other emerging markets, India and Russia… how many times have I been around the globe? One hundred, two hundred times? I do not know… This last quarter of 2005, I have been three times in China, two times in Russia, one time in Germany, in Greece, in Turkey, in Israel… the world is a village!

When I retire at the end of 2006, Dassault Systèmes is a global company, multicultural, with dozens of subsidiaries around the globe, 6000 employees… CATIA is at its Version 5 and remains our main business, but other brands have enriched our portfolio: DELMIA, ENOVIA, SIMULIA, SMARTEAM, SOLIDWORKS… and we are not talking about CAD/CAM, an acronym now obsolete, we say PLM for Product Lifecycle Management, a worldwide terminology…

In conclusion, I would summarize the extraordinary success of Dassault Systèmes as the consequence of the four following fundamentals:

1 – To be at the right place at the right time. This is the chance, or the opportunity, that only years later we realize, that we took advantage of: the IT revolution, the cold war, Dassault Aviation, then the globalization,

2 – To invent a major transformation, very far from a gadget, with a long-term vision: “the 3D for all”, the 2D to 3D revolution thanks to the IT,

3 – To make the right strategic decisions: Dassault Systèmes creation, IBM partnership, a strong ecosystem of partners, partnerships with customers, well-targeted acquisitions,

4 – To set up a robust management and execution system.

See also:

Permanent link :: http://isicad.net/articles.php?article_num=20184

|

|